Shirley Sherrod, Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, Thérèse Nelson and Me

The historic nomination of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson should be cause for great celebration. However, in the same breath, I am reminded of how far we have to go in the battle for racial equality and representation.

Federal Confirmation Hearing. Photo: Kevin Lamarque/AFP/Getty Images

The historic nomination of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson should be cause for great celebration. However, in the same breath, I am reminded of how far we have to go in the battle for racial equality and representation. Perhaps more importantly, how can we thrive within these complex institutions, and what effect will appointing this brilliant Black woman to the highest court in our country have on food policy?

Judge Jackson’s nomination makes me think of Shirley Sherrod, former Georgia State Director of Rural Development for the USDA. Mrs. Sherrod is another example of an exemplary woman to break ground and blaze trails as a first in her position. While her background as a farmer, activist, and dedicated public servant made her uniquely qualified to affect change, she was forced to resign over a falsified video supposedly showing her discriminating against a white farmer. Since then she was vindicated, offered an apology, her job back, and almost a decade later she was recently appointed to USDA Equity Commission.

When I look at her background in community development, her commitment to Black farmers is palpable. She decided to stay in the rural South and work toward change after overcoming what would have crushed many. It’s worth noting because “success” often looks differently; we tend to move away from disenfranchised communities and start anew in metropolitan cities. While there is nothing inherently wrong with moving to a new region, Shirley Sherrod is central in any conversation surrounding food or land sovereignty, she shows us all the type of impact that is possible when we make the bold choice to stay.

Although firsts in completely different fields, each and every achievement for one acts as a building block for which the next person or generation can stand upon. Furthermore, if confirmed, Judge Jackson will hear cases that have the ability to reshape the landscape of our food system. As I forge ahead on my own career path blending food policy and education, women like Shirley Sherrod and Judge Jackson inform and inspire. It must be stated that a lack of representation in the legal, healthcare, or food system does not equate to a lack of qualified and competent black professionals, perhaps just a lack of opportunity which these two women show us is an ever-evolving truth.

Thérèse Nelson started Black Culinary History in 2008 to preserve and pay homage to our collective Black culinary heritage and to directly challenge the pervasive and misguided narratives that exclude media coverage of Black chefs. I’m thankful for her facilitating my birth into the world of food writing. It’s one that often seemed abstract and ethereal in nature. While I still vacillate between pursuing a career as a chef or transitioning into academia or even law, I know my passion has a place and will guide me in the vast, interdisciplinary world of food access and sustainability.

Up until now, I have been on the periphery and now she has given me a seat at the table where we feast on cuisines old and new, ideas, and most importantly a shared commitment to cultivating our expansive communities. Through our collaboration, I aspire to further her vision and discover my story along the way.

I invite you all to come along on this journey with me! You can expect weekly posts featuring an array of content centered on Black joy. A little bit of everything, some historical pieces, content highlighting rising Chefs, monthly book reviews, and lots of food!

Let me introduce you to Carolyn Hosannah

This year we’re growing in areas like this blog and a more active Instagram feed and I want to introduce you to a huge part of this growth, Carolyn Hosannah.

Black Culinary History has been a small project with specialized support from experts like the brilliant Vonnie Williams and Kwasi Amankona who revamped the site last year and Melissa Danielle who helps moderate our Facebook group. This year we’re growing in areas like this blog and a more active Instagram feed and I want to introduce you to a huge part of this growth, Carolyn Hosannah.

I met Carolyn last year working with Dr. Jessica B. Harris developing a culinary African diaspora curriculum for the CIA (get into that as well, it was pretty darn dope). Carolyn was on our advisory committee asking amazing questions on behalf of the students and advocating for the areas of interest she knew her peers would be most curious about. Her questions, leadership, and insight through the planning process and over the course of the series were impressive, to say the least.

Her ambitions are focused on food policy. Being prepared, across disciplines, to understand and advocate for policy change that will make a better, more equitable food system. She has degrees in culinary arts, food studies and has her eye on law school to work in the footsteps of legends like Shirley Sherrod (which she’ll tell you more about in her first blog post), but in the meantime, she is stretching her writing and research muscles in service of this blog.

I hope you’re as charmed and inspired by Carolyn as you get to know her through her writing as I am. Please go on over to her Instagram page and give her a follow, keep checking our Instagram feed and this blog for all the wonderful stories coming your way, and please comment, share, and generally engage with the ideas we’re about to share.

The Warhol Mammy

When I began this project I made a very definite decision that there would be no room for confusion about the focus of this work from our name to the imagery to the bulk of the content.

Often in America Black people shy away from dealing head-on with the Black experience in lieu of the more comfortable minority experience where we can speak in generalities that seem more socially accessible for the masses. We use frameworks like BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color) so that we don’t seem militant or confrontational when trying to get our perspectives across and in the end we are left with a kind of milk toast, watered-down version of the engaged conversation we thought we were going to have.

When I began this project I made a very definite decision that there would be no room for confusion about the focus of this work from our name to the imagery to the bulk of the content. This is not to suggest that there aren’t definite parallels in other communities to the ones this project explores, simply that the purpose of this space is to examine the Black experience in all its complexity and richness. Solidarity with other communities is critical but for the purposes of this space know that the central focus is Black people.

This brings me to the Warhol Mammy and why I use it in this work. First off she’s stunning. The graphic nature of the image and the lack of equivocation about the imagery forces you to confront Blackness and the American gaze on our culture. I also think that it speaks so directly to the relationship Black people have had with America from slavery to now. We are the lifeblood of American life from the farm to the table. From birth to death the black experience has been one of service to this country and the culinary industry has been able to flourish because of our legacy of excellence.

We are less than 2 generations removed from a time when our work was considered a domestic vocation; cut to 1977 when the work got legitimized by the US government, and the cache of the industry is now worth more, and now there are articles written about why more Black chefs aren’t competitive in the culinary arts. To be clear, I think the best and most interesting culinary work should be part of every chef’s vocabulary, its the ignorance to all the amazing, passionate, inspiring, and brilliant black muses we have throughout the history of American cooking that concerns me and was one of the greatest motivations for this project.

I don’t have all the answers, i am not the authority on all things black culinary history, but i am interested in the exploration of our legacy in food that gives me the opportunity to be a working chef irrespective of race.

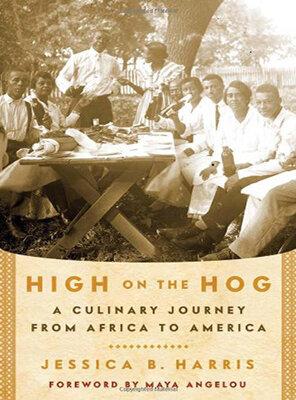

High on the Hog.

I wrote a piece for the Counter about High on the Hog the docuseries, but really I wrote about Dr. Harris’ book and the ways in which we can use her work as a tool for more rigorous examination of our collective work.

I wanted to share this piece I wrote for The Counter about High On The Hog.

It started as a piece primarily about the Netflix docuseries. I found, though, as the writing process progressed, and the world was beginning to consume the series, that the media coverage seemed to be forgetting about the book.

It felt somehow reductive to jump past a 10-year-old book that has been so instrumental in the shifts in the Black culinary cannon we've enjoyed. Stranger still to not acknowledge that Dr. Jessica B Harris' scholarship has been a 40 plus year praxis that has been clear the whole time, so my piece became more about the content of the series than a breakdown of the episodes, which I'd already done in my reader.

In that way, with a lot of help from Dr. Cynthia R. Greenlee as editor, I evolved the piece's spirit and made it about how I consumed the series and began to process its function. I also wanted to interrogate how Dr. Harris and her books have also been right this whole time.

Ultimately I found that I couldn't contextualize her books without framing the culinary zeitgeist in which she wrote them. In the end, I wrote about why reframing American cuisine through the lens of Blackness may not fix the industry but could make Black food creatives better at our work and collectively better stewards of our culture.

Anyhow, here's what it came to be, im proud of the finished product and I hope you dig it!